Let me introduce you to ‘incels’ or to give them their non-portmanteau’d title, ‘involuntary celibates’. It’s a pretty self-explanatory name for a fairly complex group. In essence, incels are those who are celibate, but not through choice. Like I said at the start, this might sum up the majority of teenagers, but beyond these lazy jokes there’s a more nefarious side. And we’ll get to that via a quick history lesson.

‘Incels’ first appeared online in the early 90s, when Canadian student Alana set up a website to share and discuss her sexual inactivity with others. One member of this community described the website in the early years as: “A welcoming place, one where men who didn’t know how to talk to women could ask the community’s female members for advice (and vice versa).” Alana’s involuntary celibacy project created a space for people of all genders to share their experiences, and a few years later the website started producing an email newsletter, where the term ‘incel’ first featured.?

But what started as a safe space for discussing relationships or a lack thereof has spawned a monster, and the word incel now conjures an image of angry teenage boys who blame women, and more specifically feminism, for all their problems. If this sounds like a mixture of pathetic and funny the rest of this story is a bit sadder because, as with everyone on the internet, if they’re angry about something they’re going to take it out on someone.?

The incel world spread beyond Alana’s corner of the internet, congregating around love-shy.com and Incel Support, and it was on this latter site where the culture began to shift to include the woman-blaming, hateful, misogynistic aspects that now characterise the incel world. In more recent years, this hatred has moved offline and into the real world. It has been reported that four mass murders – resulting in the deaths of 45 people – have been committed in North America either by self-confessed incels or by people who have mentioned incel-related names in their writings.? This includes a vehicle-ramming attack in Toronto last year and several mass shootings.?

Authorities managed to stop one attempted mass shooting as it was starting and arrested another prospective murderer who said he was planning on “killing as many girls as I can see” because he had never had a girlfriend. Other figures, such as the Las Vegas shooter Stephen Paddock – who killed 59 people and injured a further 851 – have attracted ongoing praise from members of the incel community.

It feels as though, in the age of the internet, this kind of phenomenon is become more and more prevalent. If young men aren’t being radicalised by a hatred of women they are being poisoned by hateful right-wing ideology (just look at the average turnout at an event held in support of Stephen Yaxley-Lennon, known to some as Tommy Robinson), or they’re donning their Stone Island jackets and getting in fights with people who happen to follow a different football team…?

Or is this the case? Because it feels as though it’s quite easy to pick on young men. It’s quite easy to tell these kinds of stories that paint them as thuggish types, ready to be radicalised or dragged into damaging behaviour. And maybe that’s part of the problem. If the only stories we share about young men relate to the dangers they face, the easy ways in which they’re persuaded and the vile rules they uphold, is it any wonder that they don’t believe they can be any better than this? If young men are treated like the enemy, the idea of them lashing out with hatred isn’t totally illogical.?

Let me make this totally clear: I am not defending incels. I’m not defending their hideously misogynistic language or attitudes, and the murders driven by this ideology are obviously horrific. Ideas like this need to be challenged if we see them at work among our young people. But these can’t be the only stories we tell about young men. We need to tell stories of hope – stories about young men who challenge the status quo in order to create positive change; stories that inspire young men to be better; stories that prove their identity and worth doesn’t come from how attractive they are to other people.?

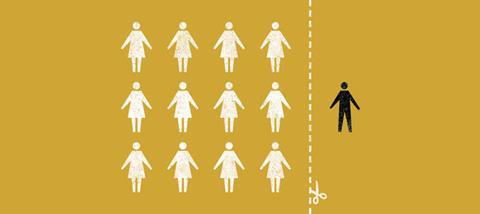

The lies underpinning the world of incels rely on them being perpetuated. They rely on young men feeling worthless. The Church should be lauded for the way it has, in places, begun to intentionally raise up female leaders, and our fear of incels should not stop this valuable practice from continuing to grow and from challenging convention. But this change cannot be pursued in a way that leaves young men behind. Similarly, as we admirably challenge sexist and misogynistic behaviour that has held women back for centuries, we need to be inspiring young men to be better rather than telling them they’re already flawed. This is a delicate balance to achieve, but an absolutely essential one to aim for.?